Bordered by Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea, tiny Djibouti has been making headlines for its dreams to become as successful as the Emirate.

Djibouti is an oasis of peace in a part of Africa marred by piracy and instability. It is this privileged position that has made the country into an exclusive military playground, home to Africa’s largest US army base and France’s biggest Foreign Legion deployment. Currently, the 53,000 civilians who visit each year are mainly business travellers, and the largely empty planes to the country are virtually devoid of tourists.

But all this looks set to change over the next two decades. This tiny speck of a country has quietly been making headlines for its aspirations to become the Dubai of Africa.

Like Dubai, Djibouti’s arid landscapes are unsuitable for agriculture, so making use of the country’s strategic position at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden – the world’s highest traffic maritime route – is critical to turn the country into a regional logistics hub.

Fourteen infrastructure projects, amounting to over $14bn, are focused on expanding Djibouti’s sea, air and land connections by 2035. The most important for travellers will be the new airport, which will separate military and commercial use and have the capacity to welcome 30 times the current number of visitors.

But what Djibouti has that Dubai doesn’t, however, is extensive natural resources along with stunning geological, marine and cultural sites.

Djibouti’s 324km coast is the gateway to the Red Sea, drawing both wreck divers and whale shark lovers from October to February when the waters are at their warmest. Stunningly empty Moucha Island, with only 20 inhabitants, and minuscule Maskali Island, famous for its corals, offer mangrove kayaking and white sand beaches, along with excellent snorkelling and scuba diving. The ongoing construction of a luxury resort on Moucha Island, however, may attract renewed interest on this empty speck of fine sand, particularly by neighbouring Ethiopians looking to enjoy the beach life they lack.

The country is packed full of geological oddities to rival Iceland’s surreal landscape. Lake Assal, 90km southwest of Djibouti city, is the third lowest point on Earth, at 155m below sea level. It’s lower than the Dead Sea – and with a higher salt concentration.

The few visitors who make the trek here will see a kaleidoscope of colours in the water, thanks to the natural biodiversity found here: green from the algae, brown from the minerals, blue from the sun’s reflections and white from the salt.

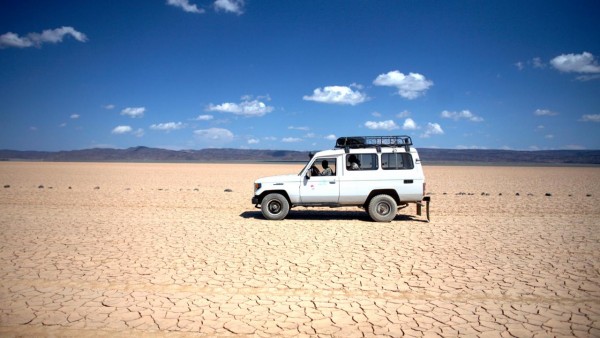

Groups of nomadic Afar tribesmen tend to their livestock, bringing herds of sheep and goats to the green pastures on the lake’s basin every morning and walking them back to their settlement in the evening when the temperature falls. Once the pastures decline, they roll up their woven mats and move their mobile settlements onto a new location.

Accommodation outside of the city is primitive, with options mostly limited to nomadic huts with the barest of beds and without running water. The government has begun to set up eco-friendly camps next to the main tourist attractions, mimicking the tribesmen’s’ igloo-type huts made of a metal semi-circle structure covered in woven mats. The new camps include solar electricity and a water deposit for the gravity shower and toilets – but a night in the open, under a carpet of stars with the Milky Way visible to the naked eye, is often a better alternative.

In Djibouti City, however, there are luxury accommodation options to be found. Dubai’s Nakheel – real estate developers credited with building such far-fetched projects as The Palm and The World – financed the construction of the grand 300-room Djibouti Palace Kempinski Hotel.

Located on a man-made island by the existing Port terminal, the hotel’s two swimming pools are inviting, if empty, and sunsets can be enjoyed from the rooftop bar, the highest point in the city. Opened in 2006, in time to host the Convention of Eastern and Southern Africa Heads of State, the hotel was Kempinski’s first property in Africa and it prematurely anticipated the country’s tourism and business growth prospects. Today it’s mostly home to the smaller armies in town that don’t own a base like Spain or Germany.

On arrival in Djibouti City, travellers will find the urban centre dusty and loud, with children and goats roaming the muddy streets. Worth visiting, however, are the two historical and heritage neighbourhoods, the African and European Quarters, which sit side by side in the city centre. The European Quarter is a mix of French and Arabic heritage, with Arabic architecture and Moorish-inspired arches, and French is still widely spoken along with Arabic. The African Quarter is a mesh of tarpaulin houses and raw streets, where the colours and smells of street food, from tandoori fish to warm Nutella-filled flat bread, fill the air.

To get to Djibouti City, a new rail line from Addis Ababa – the original French tracks from the 1900s have been in disuse since 2008 – is slated to open in 2016. The new 10-hour electric line will be a welcome alternative to the two-day dangerous road connection through dusty desert that overland travellers have had to endure in recent years.

However, due to a lack of public transportation and road signs to tourist sites, once in the country, independent travellers must hire a car with a driver who can find his way without a GPS. Blue water containers, replenished by NGOs, are the only source of water for the nomadic tribes living in temporary villages in the desert. Getting lost would mean a sure death.

Although Djibouti’s first steps towards becoming the Dubai of Africa have started with infrastructure, it’s the country’s appealing coastline and geological marvels that will intrigue visitors – and perhaps make it a better version of the Emirate. The current intrepid travellers may soon be followed by Ethiopian nationals in search of a beach getaway, and, eventually, by Gulf residents and Westerners.